In essence, the economy is the sum of an entire nation's profits...

In essence, the economy is the sum of an entire nation's profits...

People often think of "profits" as just something that corporations report. But in reality, these come from across the whole economy.

Corporate profits are the revenues companies generate less costs. Consumer profits are the revenues that folks take in less taxes and savings. And government profits are the tax and other cash the state takes in – from issuing debt and other means – less any interest expense it pays for borrowing.

Over time, the share of GDP spread across different parts of the economy, classically defined as "C" (consumption), "I" (investment), "G" (government spending), and "NX" (net exports) changes.

During recessions, government spending tends to surge as the state fills the hole in the economy created by reduced investment and consumption by consumers and corporations cutting costs.

When countries have weak currencies, net exports are likely to rise – it's cheaper for customers in other nations to buy goods from that country, as its currency depreciates.

There's also a push and pull in consumption and investment. During periods where labor markets are tight, individuals have stronger negotiating power and employees take a larger share of corporate revenues – leading to more money in consumers' pockets.

In periods when inflation is low, technology disruption is high, and labor negotiating power is weaker, corporations keep a larger share of revenue... which ends up in the hands of their investors or on corporate balance sheets. Profits rise.

As hedge-fund managers such as Bridgewater's Ray Dalio have highlighted, the U.S. is currently in a period of exceptionally high corporate earnings as a percentage of GDP. Some of the factors that have driven this – including automation, technology, and low inflation – are sustainable trends that might mean this is a new norm.

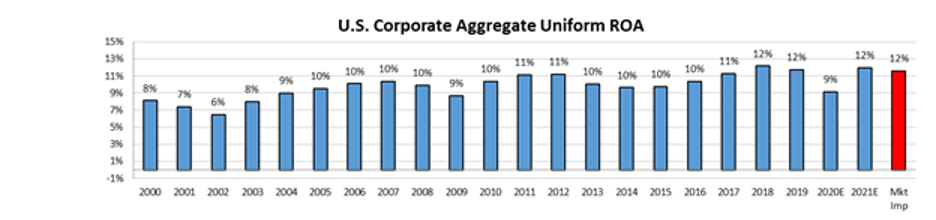

Our Uniform Accounting return on assets ("ROA") analysis of the aggregate U.S. corporate profitability confirms the secular trend in growing U.S. profitability. Returns were at their lowest in the past 20 years from 2000 to 2002, and have risen in each subsequent cycle.

While some of those trends are sustainable, Dalio argues that others are starting to reverse – such as globalization, which was significantly beneficial to U.S. corporate profitability.

Due to this (among other issues), Dalio has been calling for a "lost decade" for equity investors. He argues U.S. corporate margins are likely to come under pressure for a sustainable period of time as profits revert to a more normal share of GDP.

If Dalio is right, that would mean Uniform ROA – which is currently expected to return to cycle highs of 2018 to 2019 at current valuations, as we discussed yesterday – could be lower going forward. And that would mean near-term downside and long-term overall tailwinds for the market.

That being said, a lot of that thesis is hanging on mean reversion for corporate profitability... and that isn't a guarantee, considering the factors discussed above.

Additionally, pinning the thesis on globalization reversal already happening and leading to higher costs isn't guaranteed. Nor is it guaranteed that if it happens, corporations won't find other ways to maintain and boost profitability.

We've seen a massive shift in marketing and design over the past few decades...

We've seen a massive shift in marketing and design over the past few decades...

Rather than offering new features and intricate designs, many companies are overhauling their experiences with simplicity in mind.

If you think about how websites have changed, most of them feature fewer buttons and features, sleeker designs, and more streamlined navigation.

Companies like Facebook (FB), Twitter (TWTR), and Nike (NKE) have slowly refined their branding and web design for the modern era.

This isn't just a new, short-lived trend... Simplifying design has tangible benefits that companies are fighting for.

For e-commerce websites like Nike's, studies actually show the more "clicks" it takes to make a purchase, the more consumers are going to drop off along the way.

Likewise, simple, one-layout navigations like the Facebook timeline and the Twitter home feed keep user engagement levels high.

Our shrinking attention spans contribute to this. It's also linked to a concept called the "paradox of choice," which was originally published in a book of the same name in 2004 by psychologist Barry Schwarz.

The paradox of choice argues that in many cases, "more is less." By giving consumers innumerable options for buying products or finding information, you can actually cause decision fatigue.

Presenting a consumer with 100 options for a pair of shoes can end up having the same effect as only offering a few pairs. It might even lead to that consumer not buying anything at all as he can't make a decision – thereby defeating the purpose of providing variety in the first place!

This paradox applies more widely than just to retail items... which is why so many companies are rushing to simplify all aspects of their business, from products to web design and branding.

We have so much information thrown at us on a daily basis that people want to make fewer decisions, or they'll risk making the worst decision for a business: no purchase at all.

This very well may be linked to the investment world, too...

In the December 13 Altimetry Daily Authority, we discussed the rising popularity of passive investing, which has quickly grown from nearly nothing in 2000 to 50% of all global investments today.

This has greatly benefitted index providers like MSCI (MSCI) because more people would rather buy a stock index rather than pick and choose individual stocks.

Only a few primary choices exist when considering investing in standard market index exchange-traded funds ("ETFs"). On the other hand, if you still want some control over directing your investments to a "winner," you have hundreds of different mutual funds to choose from.

You can choose between large-cap or small-cap, growth or value, and many other variables and flavors. The same fund group might have a handful of funds in the exact same "style box," just with slight twists. It looks like the paradox of choice is also present in the investment industry.

Considering how easy passive investing choices are, while actively managed mutual funds continue to suffer from the paradox of choice, asset managers have come under pressure.

A poster child for this trend is Eaton Vance (EV).

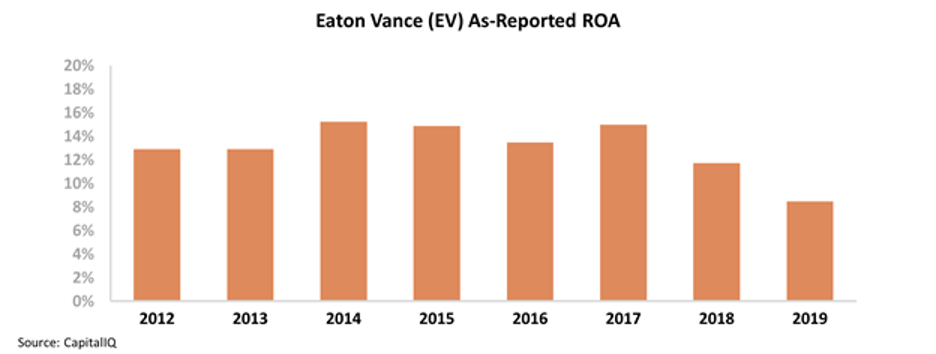

Despite the company's prominence in the asset-management industry, its as-reported profitability held up reasonably well for several years.

Since passive investing began accelerating in popularity around eight years ago, Eaton Vance's profitability was largely stable until the past few years. From 2012 until 2017, the company's as-reported ROA actually improved slightly... before falling to a low of 9% last year.

Looking at Eaton Vance's profitability trends, it looks as if the company was either able to begin adapting away from its traditional asset-management model or it protected itself from competitive pressures until very recently.

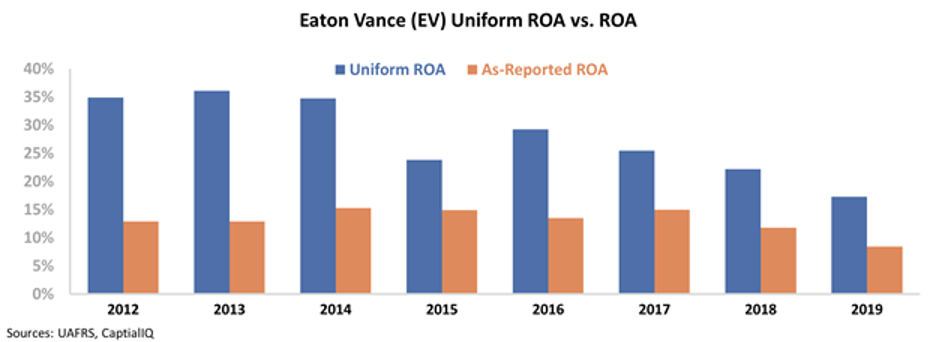

However, the as-reported metrics don't tell the whole story...

Once we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics – which adjust for misleading line items like non-cash stock option expenses, non-operating investments, and goodwill – we can see that Eaton Vance has been struggling since 2012.

While the company's Uniform ROA started higher that year around 35%, it has declined in just about each of the past eight years to just 17% in 2019. Eaton Vance's profitability has been cut in half by the rise of passive investing.

While companies like MSCI have leaned into the simplification trend in business, Eaton Vance and its 50-plus mutual funds have failed to keep up.

If Eaton Vance doesn't start to embrace the idea of simplification and the paradox of choice, the company could continue to see returns decline in the future... which could spell trouble ahead for its stock.

Regards,

Joel Litman

June 30, 2020