Joel's note: The Altimetry offices are closed on Monday for Presidents' Day, so look for the next Altimetry Daily Authority on Tuesday, February 18.

The responses have been flooding in all week...

The responses have been flooding in all week...

We want to thank all our readers for responding to Tuesday's article, where we mentioned the discussion in the Democratic presidential debates about a student-loan "jubilee."

Many of our readers mentioned the real risk of moral hazard with student-loan forgiveness, and the almost insurmountable challenges with making it work legally and logistically.

Three responses were particularly interesting...

Derek, who graduated roughly four years ago with $35,000 in debt, highlighted how the only way something could realistically be done about student-loan debt was if a potential solution also included pension reform to help guarantee Social Security benefits for the Baby Boomer generation – considering how Social Security's viability is such a serious concern for this generation.

He wasn't necessarily recommending student-loan forgiveness – he observed that student loans were a great "trial period" for Millennials to learn how to manage debt ahead of getting a mortgage. But we thought it was a novel way to get "more people under the tent" if someone wanted to have a real policy discussion.

Rob (by the way, great name!) taught us something about the real background of the jubilee. He explained:

It seems to me that the Jubilee as it was supposed to be practiced by the nation of Israel was to occur every 50 years so that if someone were to purchase land from a fellow citizen, they would do so understanding that they were only purchasing the use of the land until the next Jubilee.

Similarly, someone could sell themselves into slavery or servanthood. If the purchaser knew that in 10 or 18 or 36 years that their capital would disappear, they could make an informed decision as to whether they could recoup their investment with returns prior to that date.

Loan forgiveness or Jubilee without forewarning is disastrous to all investors and is essentially theft.

Rob's point was that jubilees worked in ancient times because they were a known, defined event... so lenders would enter into contracts to prepare for those events. Without that visibility, declaring any broad loan relief without a strong, solid framework would call into the question of legal contracts, among other issues.

The most interesting take we heard came from several people, which really got us thinking...

Several readers highlighted this idea – including David, Steve, Stephen, Glen, Gerard, and Mark...

Shouldn't the universities be the ones on the hook for this... as opposed to the government?

If a student goes to college, takes on debt to do so, and then defaults, the people who are on the hook are the student and the creditor – be it a bank, Sallie Mae, or anyone else who lent money to the student.

Once the college has received the tuition check, it's largely out of the picture. Of course, if the school has poor graduation or placement rates, it might be flagged by the government... but it has already been paid.

Some readers pointed to the sizable endowments that many universities have. Not all universities are sitting on those endowments, but the question of having universities "keep" some of their student-loan debt that they helped originate – much like how banks are now required to keep some of the mortgage debt they originate to ensure they're incentivized to underwrite good loans – might help incentivize universities to not burden their students with excessive debts.

To be clear, we aren't saying this – or anything else – is the answer. At the end of the day, those who took out the loans owe their loans.

But just wanted to thank all our readers for replying and making us consider other perspectives that are different from the economic and political orthodoxy on the issue.

This past fall, cinephiles were treated to Ford v Ferrari...

This past fall, cinephiles were treated to Ford v Ferrari...

The film tells the story of the family car company Ford Motor (F) challenging racing guru Enzo Ferrari to the most difficult race of all time.

For Henry Ford II – the grandson of the legendary business magnate Henry Ford – the 24 Hours of Le Mans race in France was a way for the company to continue innovating and appealing to the younger generation. The elder Henry Ford made his name and fortune by perfecting the assembly line – which allowed for his Model T to be sold at accessible prices.

Henry Ford II sought to improve the image of his company and live up to the legacy of his namesake by winning the 1966 Le Mans race – a 24-hour circuit dominated by Ferrari. Through a partnership with Carroll Shelby, Ford created the GT40... and the race car unseated Ferrari's domination.

Over the past 100 years, Ford has faced numerous challenges in adapting to the changing landscape of the automotive sector. In the '70s and '80s, the rising automotive industry of Japan challenged the hegemony of U.S. car manufacturers.

In 1980, Japan surpassed the U.S. in automotive manufacturing. The Japanese embraced the manufacturing approach known as kaizen, also known as "lean manufacturing." This methodology meant companies such as Toyota Motor (TM) were creating safer and cheaper cars than American manufactures like Ford during the '80s.

Ford fought back through adopting lean engineering practices of its own, along with focusing on its profitable truck lines. However, management made its smartest long-term decision in 2006...

As we discussed last month, the inability for businesses to access credit is a key component of every recession. As corporations are unable to finance, they begin to go bankrupt – which causes credit standards to tighten, thereby continuing the vicious cycle.

In 2006, Ford CEO Alan Mulally saw the writing on the wall... and understood Ford needed to tighten its belt before the next recession. He secured a sizable $23 billion loan to help restructure the business, which helped provide liquidity through 2007 and 2008. Thanks to this move, Ford was able to stay solvent during the depths of the Great Recession.

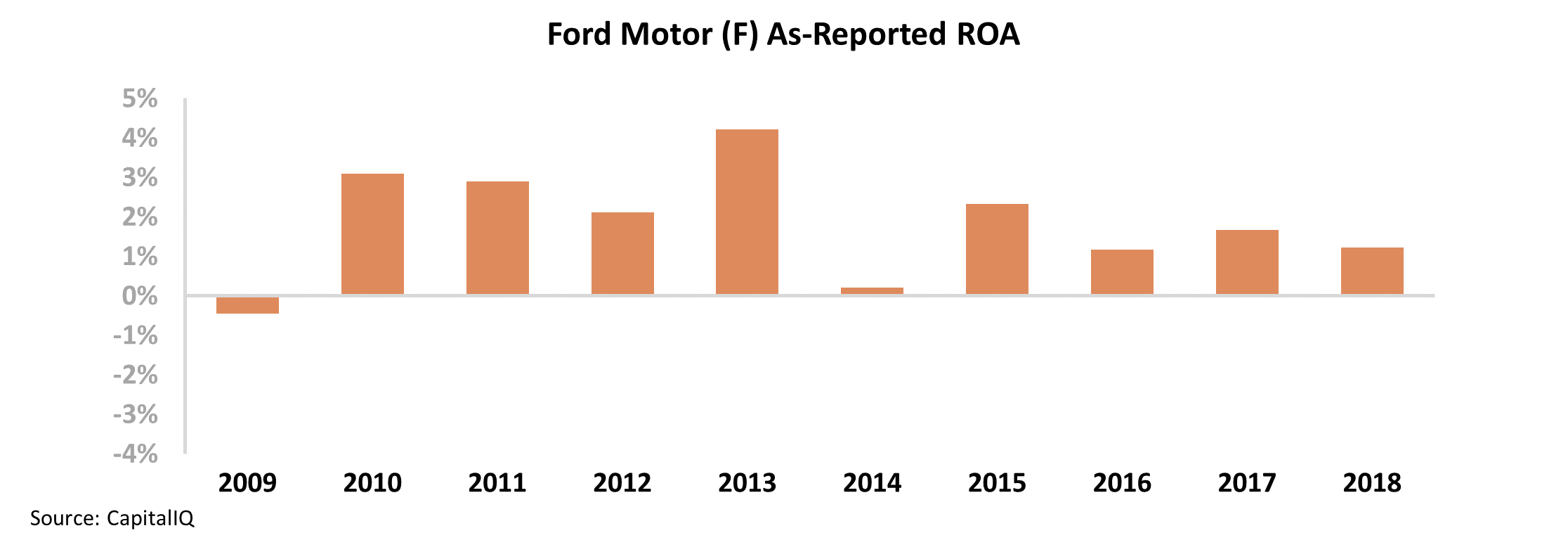

But for investors looking at GAAP metrics, it appears that Ford has never profited from Mulally's bold plan to reinvent the company. Since the Great Recession, the company's return on assets ("ROA") has stagnated below cost-of-capital levels, shifting between negative 3% and 4%. It looks as though Ford's timely debt plan served only to save the company from bankruptcy...

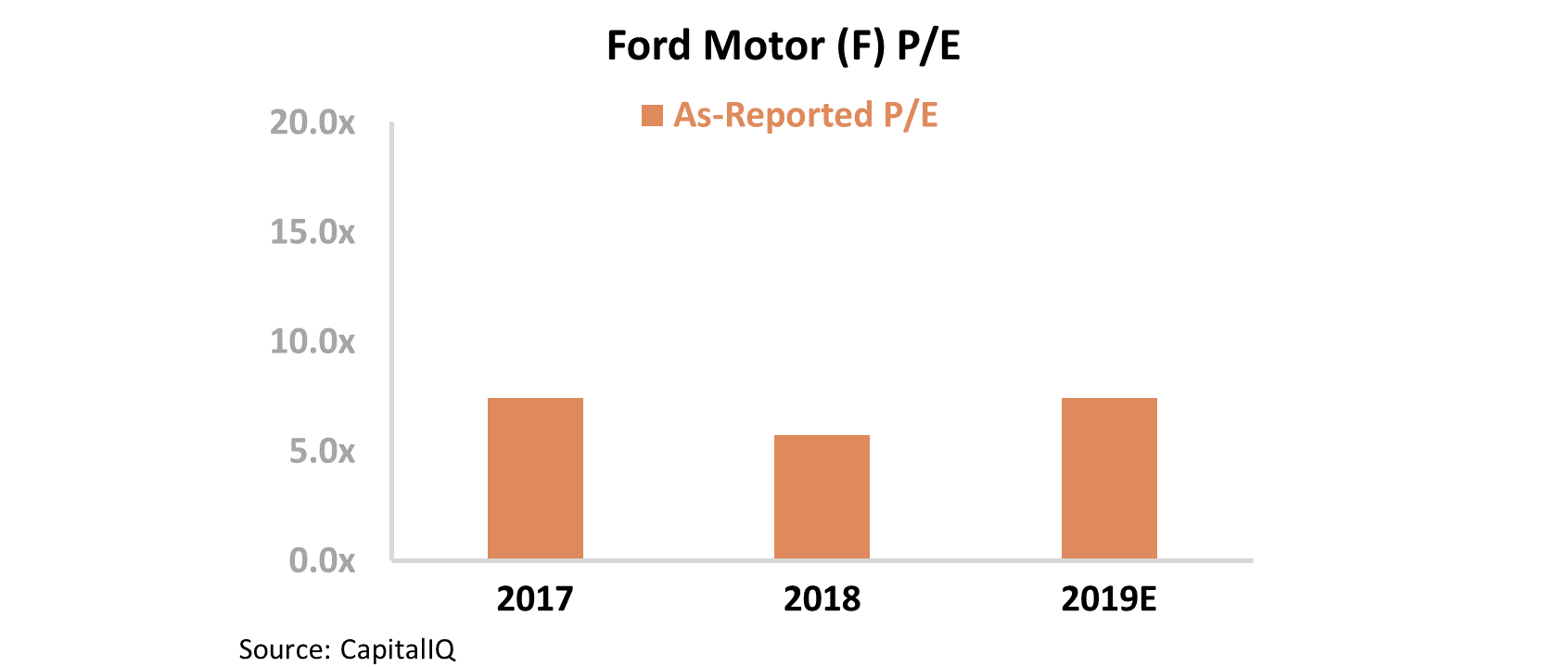

As it appears that Ford has been unable to use its capital infusion to effectively reinvest in its business, it would make sense for the company to trade at a significant discount. Therefore, Wall Street hasn't blinked an eye at Ford's current price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 7.3 – less than half of industry averages of 20 times.

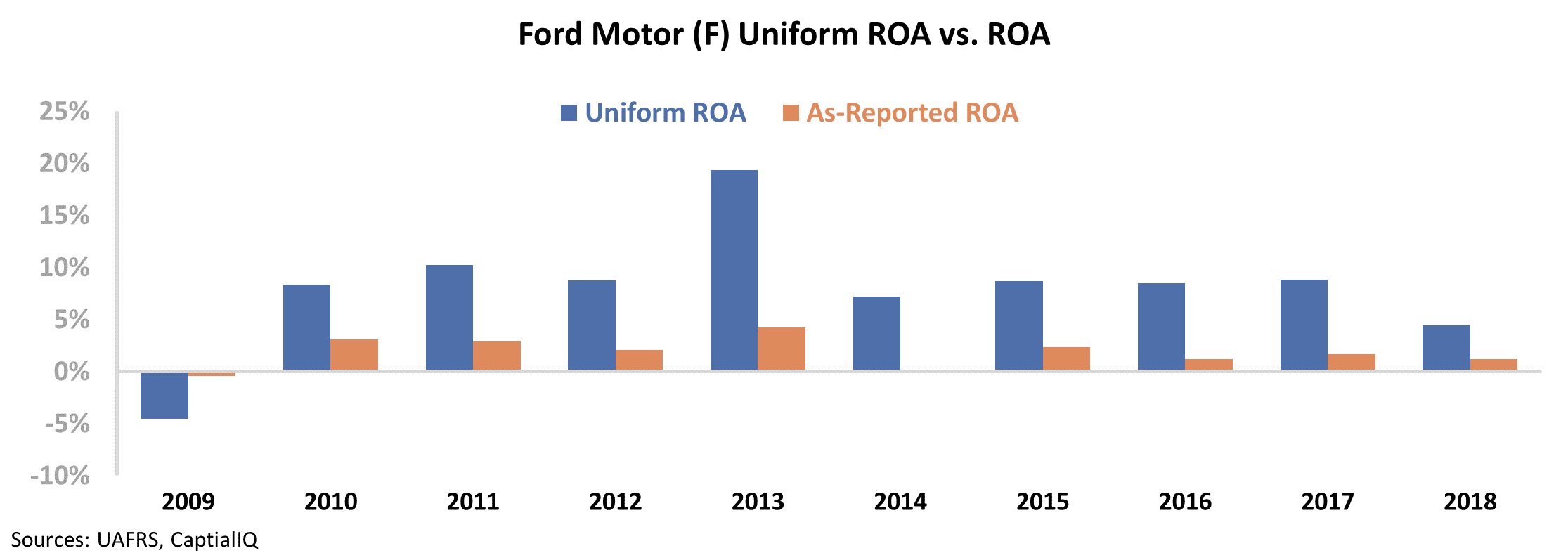

But this one-dimensional view of Ford is distorted by as-reported accounting standards. Due to the treatment of financial subsidiaries and interest expense – among other issues – GAAP accounting has missed the size and direction of Ford's profitability. Since the Great Recession, Ford has seen its profitability reach highs of 19% in 2013 – significantly greater than cost-of-capital levels.

Uniform metrics also show an important trend that the as-reported metrics fail to capture, in both directions...

Ford's Uniform ROA has been much stronger than the GAAP numbers reflect... but the company's profitability has fallen considerably from 8.8% in 2017 to 4.5% in 2018. This is a concerning sign that isn't apparent in as-reported accounting – which shows a much smaller decline.

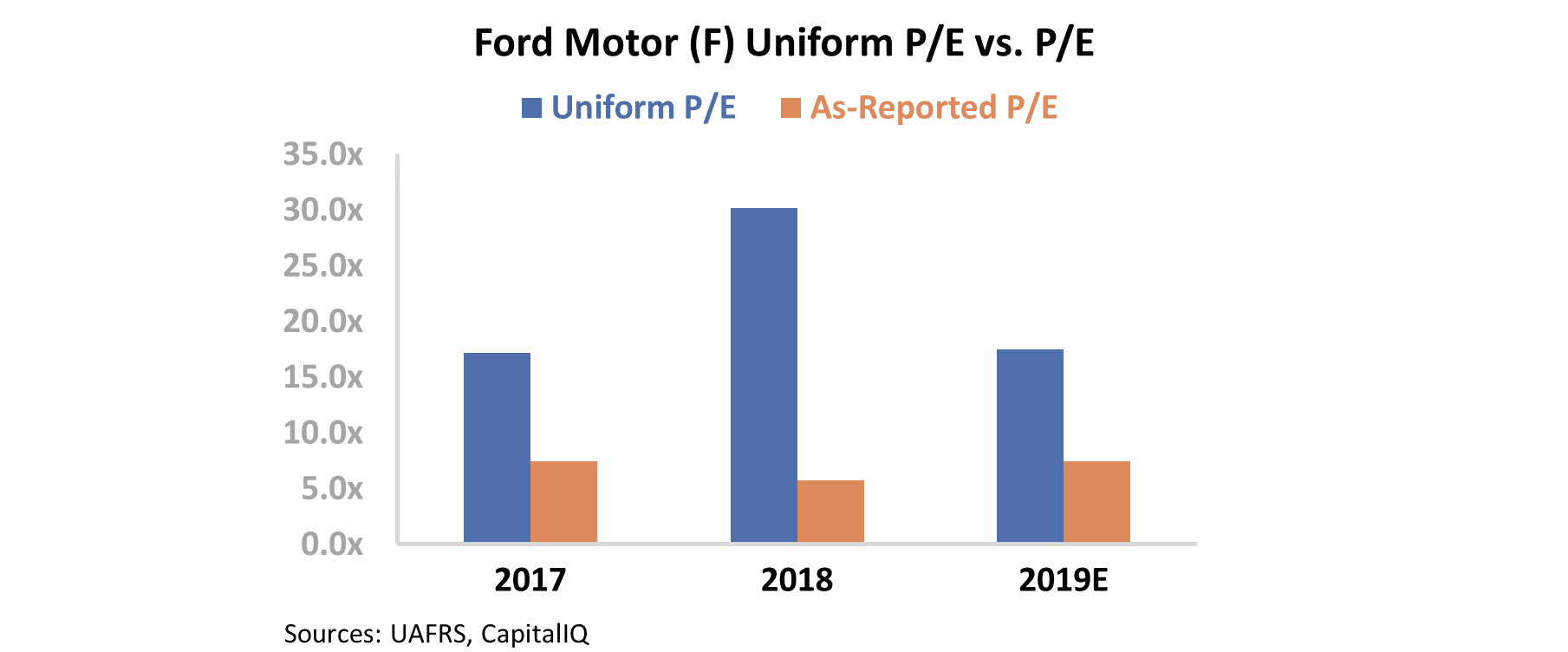

However, the market has picked up on this trend... even though as-reported metrics have not. Looking at the company's Uniform P/E ratio, we can see that Ford traded above market averages in 2018 with a ratio of 30.1 before falling to an expected 17.5 times for full year 2019.

Without using Uniform metrics, it would be impossible to spot changes like these in business fundamentals.

Due to their reliance on GAAP accounting, analysts on Wall Street have been blind to economic reality and have missed this recent downturn for Ford. While it looks like the company is a stagnant business that has plodded along for the past century, the Uniform numbers tell a different story – Ford is stronger than investors realize and has only seen recent challenges.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

February 14, 2020

The responses have been flooding in all week...

The responses have been flooding in all week...