Are we living in biblical times?

Are we living in biblical times?

Looking at the news over the past few years, it's not hard to blame people for wondering if we're living in Ancient Egypt at the time of Moses. The headlines have been wild...

- We've had rivers turning blood red...

- Frogs have overrun places they don't normally appear in...

- We've of course had a literal plague with the coronavirus pandemic...

- And now, we can add a plague of locusts to the list.

So far, it looks like we're four for 10.

Thanks to warmer weather and stronger rains than normal in North Africa, massive swarms of locusts have hatched and are making their way across Africa and the Middle East. The swarm is apparently three times the size of New York City, which is a size that's hard to even fathom.

Unfortunately, in a time of stress across the globe, this is creating another humanitarian crisis, as many of the areas impacted are war-torn (Yemen, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) or otherwise at risk of being impacted by a famine.

It's easy to focus on the scary situation here in the U.S. and across the world with the coronavirus, but even regions that haven't been as impacted by that issue are having severe problems of their own.

Stay safe, and remember that health is the first wealth.

Let's revisit the idea of monopolies and 'economies of scale'...

Let's revisit the idea of monopolies and 'economies of scale'...

In the January 21 Altimetry Daily Authority, we talked about President Theodore Roosevelt and his campaign to bust the trusts in the U.S. Roosevelt sued 45 companies under the Sherman Antitrust Act, but one company stood above the others: Standard Oil.

This was the economic empire of John D. Rockefeller, who started an oil drilling operation in 1863. This small outfit quickly grew to encompass all of Cleveland's oil drilling. However, it wasn't the oil rigs that built Rockefeller's fortune... He became the richest man in U.S. history by horizontally and vertically integrating his business.

Rockefeller took the money he made from his Cleveland operation to buy oil processing fields, marketing operations, and transportation companies. He took out competitors, customers, and suppliers.

By owning the entire supply chain, Rockefeller was able to undercut his competition and buy them out. By integrating and leveraging "economies of scale," Standard Oil couldn't be slowed down by free market forces.

At its peak, the oil empire accounted for a massive amount of the gross domestic product ("GDP") of the U.S. and controlled more than 90% of the U.S. refining business. Standard Oil was able to refine oil at low costs and sell for a high price, which attracted the ire of Roosevelt and the U.S. government. In 1911, in a landmark case, the U.S. Supreme Court split Standard Oil into 34 separate entities.

But modern companies haven't forgotten Rockefeller's business lessons. Over the past 40 years, there has been a wave of companies who have sought to strategically acquire competitors or suppliers to improve their economies of scale.

In 1997, plane maker Boeing (BA) acquired aerospace firm McDonnell Douglas, in order to expand its portfolio into defense and realize cost benefits to its manufacturing. We've seen the same trend in the health maintenance organization ("HMO") space, as firms such as UnitedHealth (UNH) and Anthem (ANTM) have horizontally integrated to leverage their combined scale.

And today's oil companies are doing the same thing. Two of the largest businesses left over from Standard Oil were Standard Oil of New York and Standard Oil of New Jersey. After they both went on to steadily acquire competitors throughout the 20th century, they changed their names to Mobil and Exxon, respectively. In 1999, these two oil juggernauts merged to become ExxonMobil (XOM).

Another company that has understood the power of economies of scale is Brazilian private-equity ("PE") firm 3G Capital. 3G turned InBev into a goliath that manufactures beer across the globe... and in 2008, InBev acquired competitor Anheuser-Busch to become brewing giant Anheuser-Busch InBev (BUD).

In 2015, 3G bet big in the consumer space again with the merger of H.J Heinz and Kraft Foods to create scale and save cost in the new company Kraft Heinz (KHC).

The PE fund's goal in both these investments was to build massive businesses, benefit from economies of scale in sourcing and with distributors, and drive down costs through a "zero-based budgeting" approach.

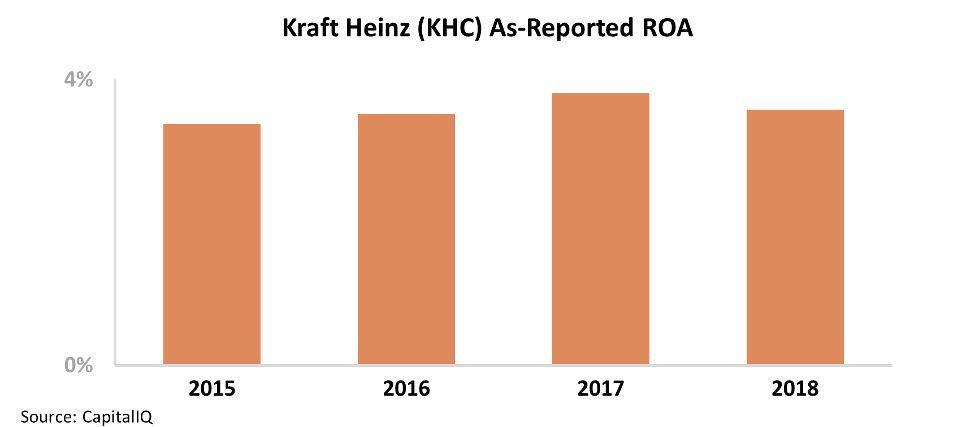

However, by looking at the performance of Kraft Heinz since its inception in 2015, it would appear that 3G has missed the mark. Using GAAP accounting metrics, Kraft Heinz has seen its return on assets ("ROA") plateau between 3% and 4% – below cost-of-capital levels.

Simply by looking at the as-reported numbers, it would make sense to write off 3G's move of consolidation as a wasteful exercise in PE deals. However, this ignores the truth of Uniform Accounting hiding below the surface...

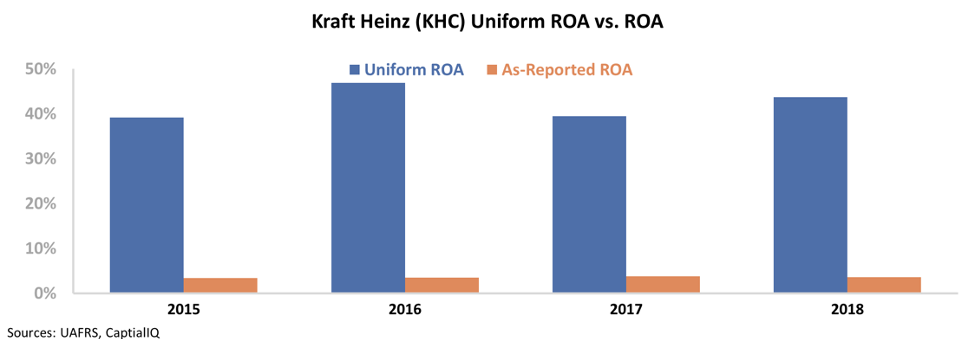

Once we account for the significant amount of goodwill in the business, along with making other adjustments, Kraft Heinz's real performance stands in stark contrast to the as-reported data. In reality, the company has seen returns climb to 44% in 2018. Furthermore, Kraft Heinz's ROA has been trending higher since 2015. Take a look...

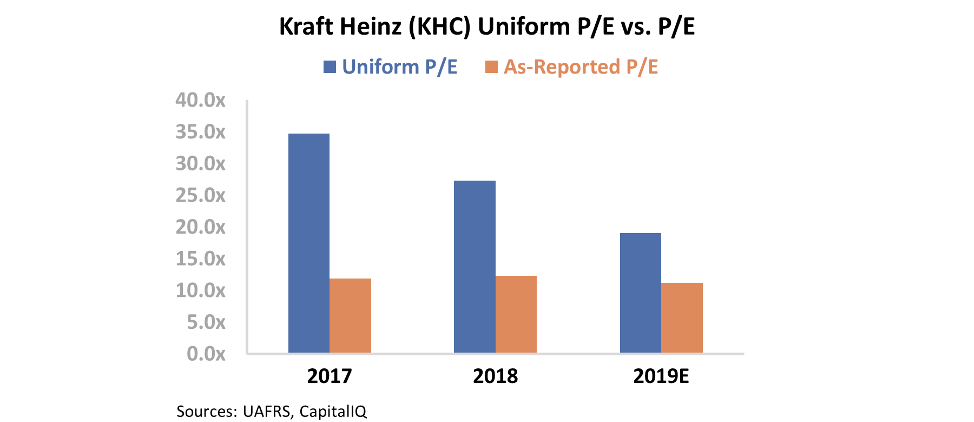

And based on GAAP accounting, Kraft Heinz's price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio has the same problem as the company's ROA. The company's as-reported P/E ratio is 12, indicating that the firm is priced for a poor return. However, Kraft Heinz's Uniform P/E ratio is substantially higher at 19 – right at market averages.

In reality, the 3G deal to merge Kraft Foods and H.J. Heinz has created significant value for the two firms, as both companies have improved their efficiencies with scale. And smart investors have realized that... and paid reasonable valuations for the combined company.

This isn't a low-return company the market hates... It's a high-return business that investors are comfortable paying up to own.

When you look at the right numbers, you can see the value of the business strategies that Rockefeller realized more than a century ago.

Regards,

Joel Litman

April 3, 2020

Are we living in biblical times?

Are we living in biblical times?