Joel's note: The Altimetry offices are closed tomorrow and Wednesday for the Christmas holiday, so look for your next Altimetry Daily Authority on Thursday, December 26. Have a great holiday, and we'll see you later this week!

Is it the 'lay of the land'? Or 'how the land lies'?

Is it the 'lay of the land'? Or 'how the land lies'?

I was on the phone recently with a client – one of the biggest hedge funds in the world – based in Stamford, Connecticut. The call was with a colleague out of the firm's Hong Kong office.

We were sharing notes on forensic accounting, particularly when looking for "financial red flags" at earlier-stage companies and initial public offerings ("IPOs")...

Before diving into the numbers, good forensic analysis first demands a look into the "lay of the land." My colleague on the phone, who speaks the Queen's English, would say, "How the land lies." I kind of like that version.

When looking for financial red flags, you must first examine the players and the process surrounding the financial statements at a company.

For example, in 2014, we created a list of 57 publicly listed companies in the U.S. with "bad player" Certified Public Accountant ("CPA") firms. Examples of these included:

- A complex international company reporting several hundred million dollars in global revenue... with an auditor out of Idaho with only one partner and a handful of employees.

- A group of companies – all related to each other in some way – under audit by the same CPA firm that had no other audit clients except this group of businesses.

- Companies under audit by otherwise unknown CPA firms with "highly questionable" office addresses in Queens in New York City and voicemail-only phone numbers.

And one last important note... for each of the 57 businesses on this infamous list, the CPA firm had previously been found in violation of audit standards according to the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board ("PCAOB").

Over the course of a year, while the overall stock market was up 10% or more, 51 of these companies saw their stock prices fall. The average change in stock price of all 57 was negative 50%.

Examining "how the land lies" in a company's accounting process goes a long way in determining whether or not the company may be a worthy investment.

As regular Altimetry Daily Authority readers know, it's important to clean up the accounting. But it's even more important to get the accounting right. If you don't, it doesn't matter how much you "cleaned it up"... you're still working with bad numbers.

As we've said before, deep bear markets and recessions don't occur without a negative credit event...

As we've said before, deep bear markets and recessions don't occur without a negative credit event...

Here at Altimetry, we focus on debt when talking about the next recession – whether it's corporate debt that could come due, government debt changing prices, or investor debt for buying on margin. This is because every modern recession has started with a debt crisis.

Be it the Panic of 1907, the Great Depression, the Roosevelt Recession, the credit crunch in 1970, the Latin American crisis in 1982, the savings and loan crisis throughout the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis, the Great Recession, or even the dot-com bubble... At the beginning of each – or throughout each – was a debt crisis.

However, we haven't yet talked about the debt which brought the market to its knees 11 years ago... It's the debt that's most important to you and me.

Household debt is just as important an indicator of a recession as any of the other types of debt we've already discussed. And monitoring it is vital to understand if we don't wish to walk headlong into another Great Recession.

While there are a lot of moving parts that caused the Great Recession, most folks know that the underlying issue was the overbought mortgage market. With investors looking for alternative assets to place their funds, banks created an asset class called the "mortgage-backed security." (This financial instrument pays out the interest of a group of mortgages.)

The cash flows from assets were then transferred to investors through such vehicles as collateralized debt obligations. Furthermore, investors could buy credit default swaps, which acted as insurance on the underlying mortgages. With the ability to now move risk off their books, banks sought to write as many loans as possible. What all of these asset classes relied upon, however, was the average homeowner paying his mortgage on time.

Once interest rates began to rise, those with adjustable-rate mortgages could no longer make their home payments. As defaults skyrocketed, all of the assets that were tied to mortgages failed... and the house of cards collapsed.

The Federal Reserve had to step in as a lender of last resort to banks – and to a certain extent, to the market as a whole – as capital dried up. With little ability to roll their debts forward, corporations were forced into bankruptcy as well.

This is why mortgages specifically – and consumer credit in general – are so powerful and so important to study.

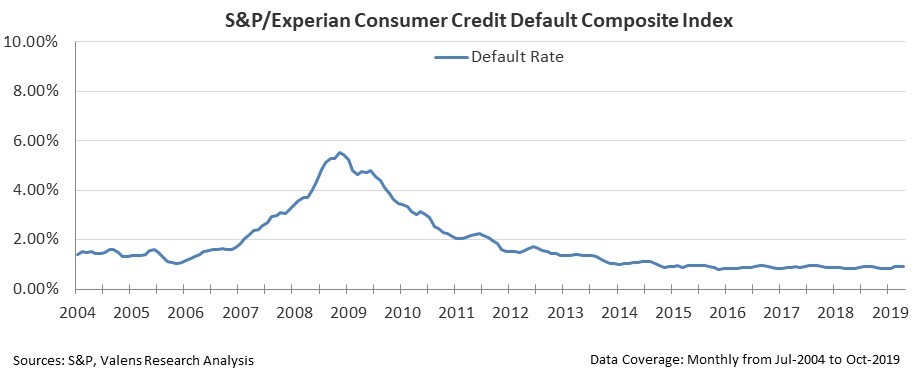

One way that we keep track of consumer credit is through the national S&P/Experian Consumer Credit Default Composite Index. As you can see, after peaking above 5% in 2008, the index is currently just below 1%....

However, getting an accurate picture of credit risk for U.S. households requires another step deeper. While debt defaults didn't happen overnight, defaults are a relatively lagging indicator for the current health of America's balance sheet.

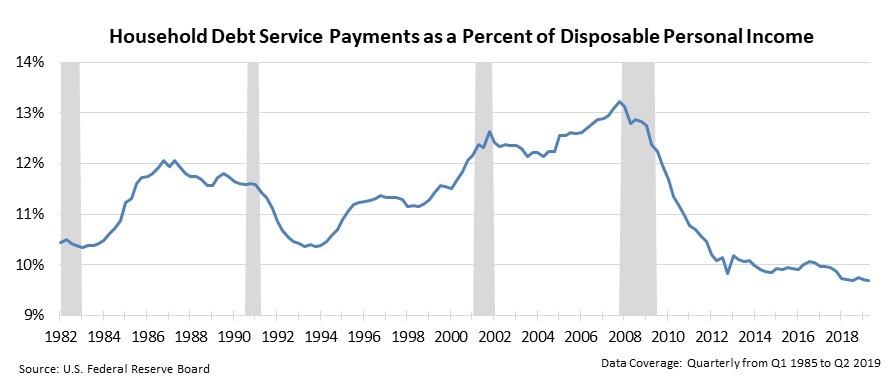

A stronger way of measuring current credit risk for homeowners is looking at debt payments as a percent of disposable income. If the percent of debt payments gets too high, the risk of default looms as it becomes harder and harder to service debt.

However, in 2019 debt service payments as a percentage of disposable personal income are at their lowest level in the past 38 years. After peaking above 13% in 2008, this percentage has trended steadily lower as households have shied away from debt after the Great Recession...

With such a low debt burden, there's still room for higher levels of consumption from households that don't need to service debt. Furthermore, the risk for widespread default like in 2008 is minimal, as the average household has a larger income buffer before being forced into default.

After such an impactful recession, Americans have generally been hesitant to take on debt. The byproduct of this is that the risk of household debt default is near all-time lows.

While credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations still exist, they're no longer the ticking time bombs they were in 2007.

Doomsayers continue to call for an imminent recession and collapse of credit markets. This is just yet another factual data point we look at on a regular basis that gives us confidence that those concerns couldn't be further from the truth.

Without a debt crisis, a recession and a severe bear market just doesn't occur. And with every credit market we look at flashing "all clear" signals that don't cause concern, there's still reason to expect the market to rise going forward.

Regards,

Joel Litman

December 23, 2019

Is it the 'lay of the land'? Or 'how the land lies'?

Is it the 'lay of the land'? Or 'how the land lies'?