Maybe he was hoping this would make the market change its mind about his company...

Maybe he was hoping this would make the market change its mind about his company...

In October, we wrote about how steel company Cleveland-Cliffs' (CLF) CEO Lourenco Goncalves showed his displeasure with analysts on recent earnings calls, claiming they didn't understand his business. We also highlighted how the market might not understand the company's real profitability.

Earlier this week, Cleveland Cliffs announced it is acquiring AK Steel (AKS) for $1.1 billion. Perhaps Goncalves sees Cleveland Cliffs' strong as-reported 13% ROA versus AK Steel's as-reported 5% ROA and thinks he can improve that business, too...

But both AK Steel and Cleveland-Cliffs have a weak 4% to 5% ROA once Uniform Accounting removes the accounting noise.

This is yet another example of how Goncalves may be pointing the finger at the wrong person when complaining about why the market doesn't like his company...

One of my first jobs was at my local food shop, The Green Spot, near Waterville, Maine...

One of my first jobs was at my local food shop, The Green Spot, near Waterville, Maine...

I was hired by the Athanus sisters – founders of The Green Spot – to transport local produce to the store. I would drive from farm to farm, picking up whatever was on their list for the day. One day might be sweet peas from a local farm, and fiddleheads from Biddeford the next.

For the uninitiated, fiddleheads are the young fronds of the ostrich fern – curly, bright green, and delicious when served steamed or sautéed between a piece of fish and some potatoes. They're a bit of a delicacy in northern New England and they're only in season for a few weeks every spring.

Starting in May, the "Green Spot Sisters" would instruct me on which farms to travel to first to ensure they got the best fiddleheads. I was never fully sure how they knew which farms have the best crops, but they always knew.

Eventually, I had to ask for the secret. There were a lot of different variables that went into it, but it turns out, one part of it was quite simple... Good fertilizer produced the best fiddleheads.

Not all suppliers are created equal.

When most people think of fertilizer, they think of Miracle-Gro or Scotts Turf Builder, and don't much think what's in the product.

But not all fertilizer is the same. In fact, there are three particular types of fertilizer that are the most common: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (sometimes called potash).

Depending on the quality and type of the soil where you want to plant, you most likely want to use different fertilizer blends.

For context, Miracle-Gro is 15% nitrogen, 30% phosphorus, and 15% potassium fertilizer. Scotts Turf Builder is 32% nitrogen and 10% potassium, with no phosphorus.

Nitrogen was historically heavily leaned on for fertilizing. But research shows utilizing fertilizers with potash and potassium makes for healthier, longer-lasting crops than simply using nitrogen fertilizer on its own.

However, potassium and potash fertilizers are less common, and as a result, it's much easier and cheaper to get nitrogen fertilizer.

Within the chemical and fertilizer industry, potassium and potash fertilizers tend to have pricing power, while nitrogen fertilizers are treated as a commodity and are therefore sensitive to price changes.

Potash is such a small market that for some time there was a duopoly between Canada and Russia/Belarus, which kept prices high.

Because of that, potash and potassium fertilizer companies tend to earn stronger returns through a cycle.

There's no opportunity for a similar duopoly – or for suppliers to have pricing power – in the nitrogen fertilizer market. Since nitrogen fertilizers are mostly made directly from natural gas, those fertilizer-chemical companies tend to see returns move up and down with the commodity.

And one such company is CF Industries (CF) – it's a great case study into the ups and downs of a commodity cycle-driven business.

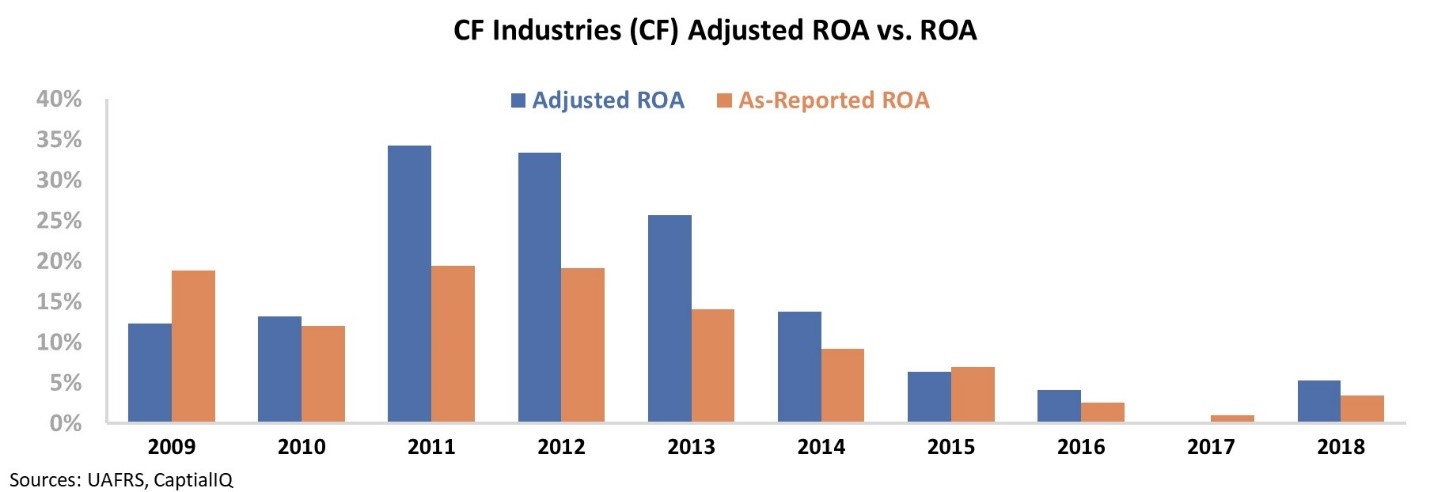

Both on an as-reported and a Uniform Accounting basis, CF Industries saw a strong return on assets ("ROA") in the early 2010s as demand for nitrogen fertilizer was high.

Since 2014, this industry has flipped. Production flooded the market as there were industry-wide supply increases – which also drove down prices – that sent CF Industries' ROA to levels near 0% by 2017...

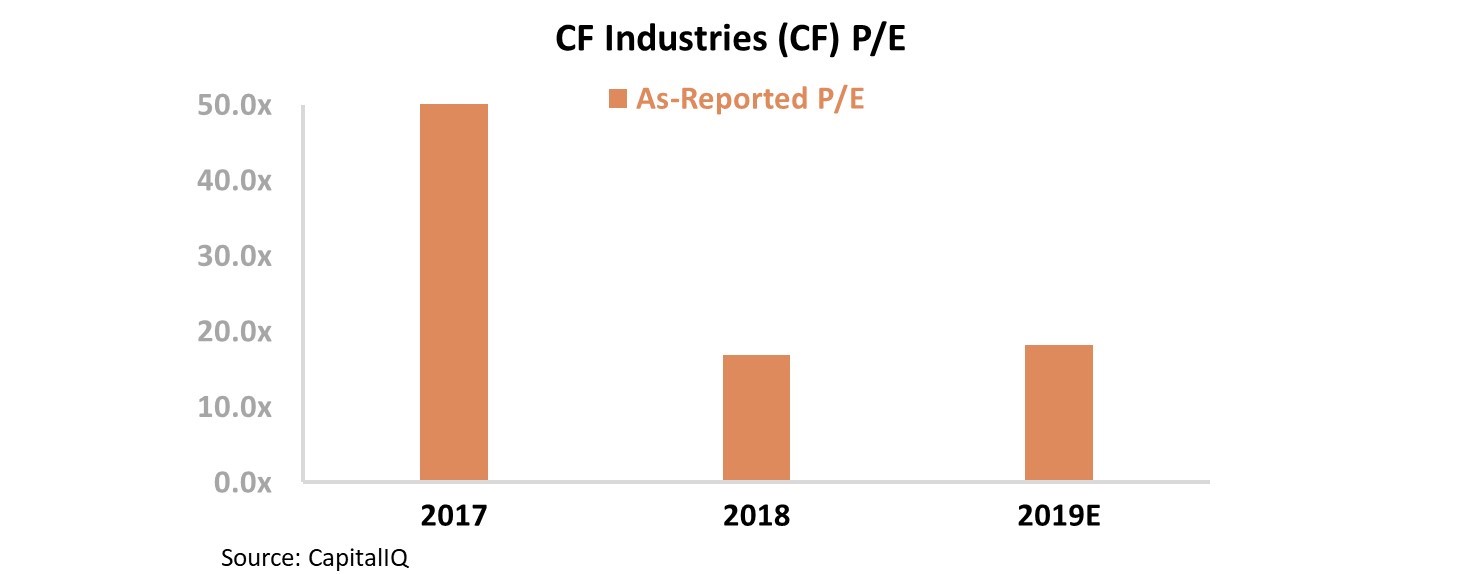

The market appears to be aware that CF Industries is a commodity business and expects these low returns to continue. The company is trading at fairly inexpensive levels with an as-reported price-to-earnings ("P/E") ratio of 17 to 18 over the last two years – a reasonable P/E ratio on low earnings. Take a look...

Investors might think that with a somewhat low P/E ratio – and the potential that CF Industries could see earnings rebound if the cycle flips – this could be an interesting buying opportunity at such inexpensive levels.

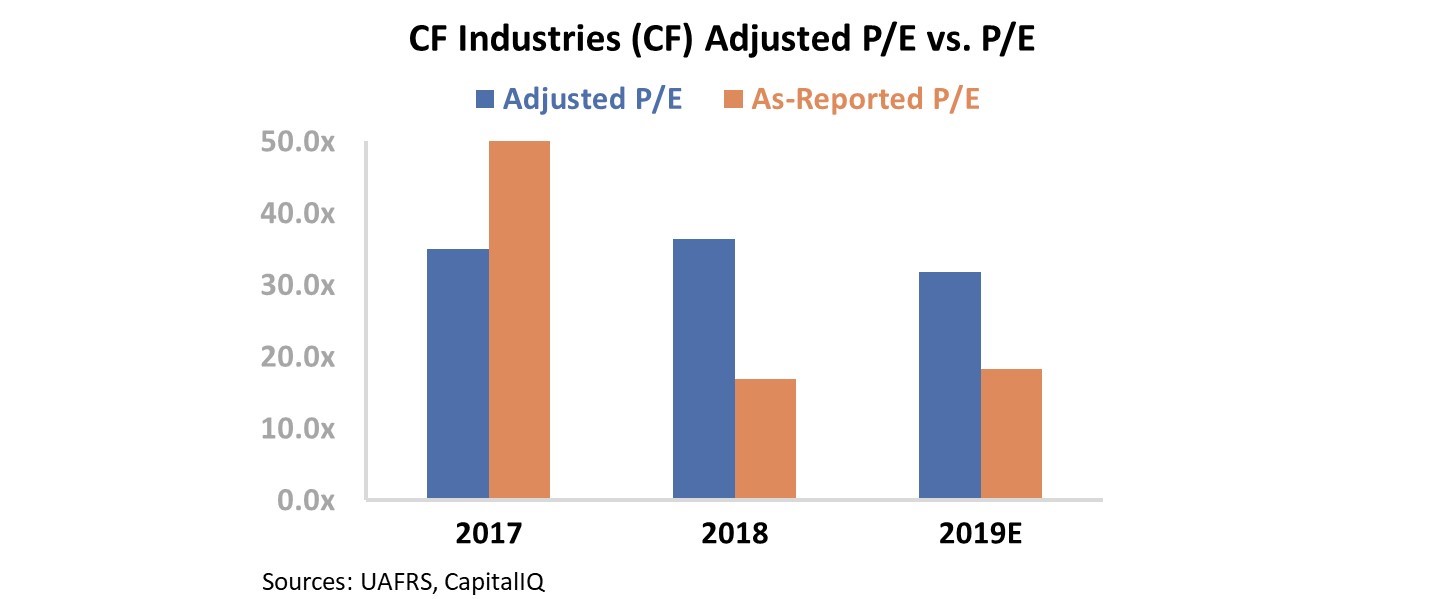

That said, when we look at CF Industries using our Uniform Accounting metrics, we see a completely different story...

Even though the company's ROA looks fairly similar on either an as-reported or a Uniform basis, that does not necessarily hold true for valuations.

Once we adjust for accounting distortions present in as-reported financial metrics – such as the mistreatment of items like goodwill, interest expense, and operating leases – CF Industries looks far more expensive.

You see, on an as-reported basis, it looks like a company that has become progressively cheaper as the commodity cycle has crashed. Conversely, we can see that CF Industries' Uniform P/E ratio has remained around 30, well above corporate averages and firmly in "expensive" territory...

When looking at a commodity business like CF Industries, accounting distortions can make it difficult to properly value the company during a change in the commodity cycle.

Regards,

Joel Litman

December 5, 2019

Maybe he was hoping this would make the market change its mind about his company...

Maybe he was hoping this would make the market change its mind about his company...