We've found 'Groupon 2.0'...

We've found 'Groupon 2.0'...

As subscribers to our Altimeter tool know, we aren't fans of online retailer Stitch Fix (SFIX). We've highlighted the company twice this month for a specific reason...

Stitch Fix is a ticking time bomb that's following in the mold of several other "fad" companies that have come around in the past 10 years. – think Groupon (GRPN), GoPro (GPRO), and Grubhub (GRUB), among others.

Once these companies start making money, the market starts to pay a premium for them. Investors saw the gigantic total addressable market ("TAM") for Groupon as all of consumption. GoPro's TAM was anyone doing anything they want to show off on video. And for Grubhub, its TAM is all of food delivery.

Just looking at each in a snapshot in time, their fundamentals also justified market excitement.

Groupon had 45% revenue growth with almost 10% Uniform earnings margin in 2012, and was able to operate with basically negative working capital. Since customers paid Groupon before the company had to pay its vendors, this was a business that had phenomenal economics.

When GoPro went public in 2014, it had 54% Uniform return on assets ("ROA"). It was a cash-generating machine.

Grubhub's Uniform ROA peaked at 59% in 2015, and the company has grown by 30% a year since it went public in 2014.

While each company performed impressively for a period of time, there was a key problem that anyone studying their business model could see: They didn't have any genuine assets that another competitor couldn't recreate.

When I teach at MBA programs, one thing I focus on is a "return-driven strategy." It's a framework that a colleague, Dr. Mark Frigo, and I codified two decades ago. And it's as relevant now as it was then...

The idea is that any company can create long-term sustainable value if it has a few key traits, and focuses on specific things when operating its business. A company needs genuine assets, an awareness of how the business is evolving, and an ability to understand and track key performance indicators ("KPIs") to be able to succeed.

A company also needs to do key things like partner deliberately, innovate and deliver products successfully, target appropriate groups, and fulfill otherwise unmet needs to be able to generate value.

If you don't have genuine assets – something you can do that no one else can do – you don't fulfill an otherwise unmet customer need, you can't succeed in the long term.

For Groupon, GoPro, and Grubhub, none of these companies do either of these.

Anyone could go out like Groupon and get shops to give special discounts to get people to come to the store. It's why as soon as Groupon started succeeding, competitors like Gilt came into the market with Gilt City.

Any video camera or camera maker could make a camera with a more sturdy case so it wouldn't break while doing something extreme, or make easier ways for people to upload their videos... hence why GoPro never moved beyond a niche business.

And as we've previously discussed with Grubhub, restaurants don't just have to partner with Grubhub as a delivery service... they can partner with as many as they want, including with local startups.

None of these firms had the genuine assets to enable them to create long-term value. Their business models could be easily recreated elsewhere. And Stitch Fix has the exact same issue...

Stitch Fix's business is to ship packaged cardboard clothing "trucks" to people each month, tailored to their fashion. If you like the clothes, you can buy them... Or you can ship them back.

But any company can do this... and others have done so. Businesses such as Rent the Runway, Nordstrom's (JWN) Truck Club, and even individual brands have come out with similar solutions after seeing Stitch Fix's popularity.

But Groupon, GoPro, and Grubhub all saw their returns plummet from high double-digits to current levels at less than 10%... and Stitch Fix is on the way. And in this case, the market doesn't realize it yet. Stitch Fix trades at 9 times book value, and sports a massive Uniform price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 184.

And adding fuel to the fire, Stitch Fix disappointed on earnings last week. The company reported a third-quarter earnings per share ("EPS") loss of $0.33 versus expectations for a $0.15 loss. And revenues fell from $409 million in the same period last year to just $372 million, missing the forecast for $418 million.

We don't want you losing money on our watch... Stitch Fix is just another fad company, and investors should avoid it.

A friend of Altimetry likes to say that data is the 'oil of the future...'

A friend of Altimetry likes to say that data is the 'oil of the future...'

We've mentioned it before, and we're not backing down. Even as people continue to need traditional currency, data is becoming more valuable and more entrenched every day.

In the April 17 Altimetry Daily Authority, we talked about how all companies – from Silicon Valley tech giants to risk-assessment firms like Verisk Analytics (VRSK) – are scrambling to collect as much data as they can.

It's why social media platforms are free... They make plenty of cash on advertising and other ways of monetizing their users' data.

That's why we've called data the "currency of the future." As an economy, we're expanding past the old industrial, asset-heavy model into a more thought- and knowledge-driven model.

Instead of talking in terms of hard assets, the world's biggest firms deal in intangible assets like data and content.

But there's an argument to be made that – as John Sviokla, a former Harvard professor, ex-vice chair of Diamond Management Consulting, and innovation lead at PwC – says, data is more like the "oil of the future" than the currency of the future.

Unlike currency, raw data is a commodity. It's available everywhere, it's not always of good provenance, and on the surface it's not very useful.

In order to make data useable, it needs to be "refined"... much like oil. This can mean different things in different contexts: Data needs to be validated, cleaned, and analyzed for it to be valuable, much like oil needs to be processed to turn it into gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, products for plastics, and other chemicals.

When social media companies like Facebook (FB) and Twitter (TWTR) sell data, it's delivered in specific ways – often as demographic reports or direct access to users' preferences and profiles.

Without the social media firms first ingesting and sorting through the data, it wouldn't be useful to advertisers.

One of the first industries to discover that data had to be refined to be useful was the consumer credit rating industry. By formalizing our purchase and payment trends, companies like Equifax (EFX), Experian (EXPGF), and TransUnion (TRU) could help make the financial industry more efficient.

These companies realized they could provide lenders with consumer credit data (which has come to be known as our credit score), while also providing consumers with some level of credit protection and insights on how to improve their credit scores.

Ever since, the "big three" firms have been in a race for consumer data to refine and profit from.

Despite the company's major security breach in 2017, Equifax has been one of the leaders in collecting and refining consumer data.

That said, its profitability has been lackluster... even prior to the data breach. This potentially calls into question the value of the data Equifax was gathering.

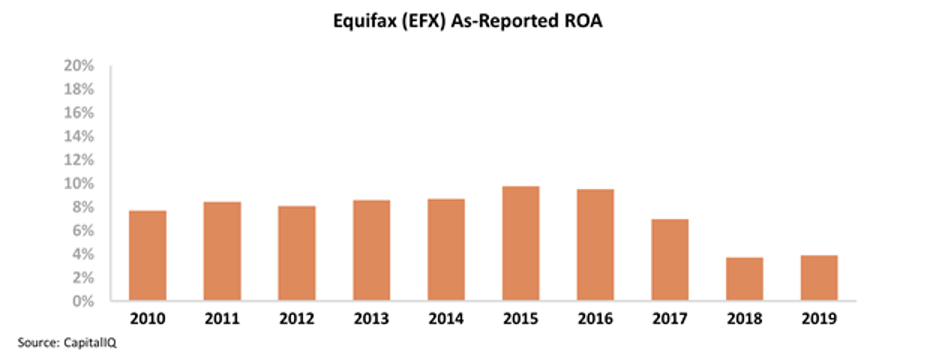

Over the past decade, the company's ROA mostly hovered around 8% to 10%, before tapering off during the past three years to 4% because of the breach.

Given that the long-term corporate average ROA is 6%, this isn't particularly impressive.

To Equifax's credit, its ROA was steadily improving through 2016... though not at a great rate.

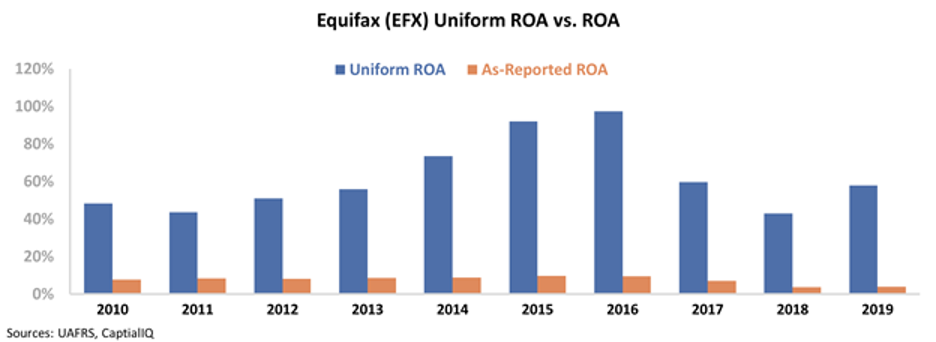

However, the as-reported metrics suffer from a number of distortions that make it difficult to assess just how profitable Equifax really was.

Once we clean the company's as-reported financial metrics – adjusting for misleading line items like goodwill, one-time special items charges, and non-cash stock option expenses – we can see that Equifax's profitability is much more impressive.

From 2010 to 2016, Equifax's Uniform ROA expanded from 48% to a peak of 97% – more than 15 times long-term corporate averages.

Of course, the data breach did have a tangible effect on the business. But despite that disruption, Equifax's Uniform ROA is still 58% compared to its as-reported ROA of 4%.

The difference between the as-reported and Uniform metrics is night and day. As-reported ROA fails to capture the value of Equifax's ability to refine and utilize data, making the company look like it hasn't been able to recover from its data breach.

In reality, Equifax is more profitable to begin with and is already starting to accelerate its fundamentals... which you might miss if you relied on as-reported data alone.

Regards,

Joel Litman

June 18, 2020

We've found 'Groupon 2.0'...

We've found 'Groupon 2.0'...