We let out a collective groan last week when the news broke about ride-sharing company Uber (UBER)...

We let out a collective groan last week when the news broke about ride-sharing company Uber (UBER)...

The company keeps expecting to work miracles in markets that are too competitive for it to successfully monetize. And regular Altimetry Daily Authority readers shouldn't be surprised by our reaction when reports surfaced that Uber is trying to buy food-delivery company Grubhub (GRUB).

We've explained in Daily Authority issues why we think the fake platform businesses won't ever sustainably make money. And we've specifically talked about both Uber and Grubhub's issues in the past.

There's a misnomer in the market right now that marketplace companies are platform businesses that can generate massive profitability when they scale. The distinction between a real platform company and the fad platform businesses comes down to a question of having an economic moat and switching costs.

To be a true, sustainable platform that can earn high returns for a long period of time – and using the "flywheel" effect of more revenue translating into greater returns – a company has to do something that can't easily be replicated by anyone else.

A great example of a real economic moat is a company like Visa (V). The financial-services firm has built the capability to process a massive amount of transactions on a seamless, second-by-second basis. Visa has high security for those transactions, and has also built the largest matrix of merchants across the globe. It would take years (if not decades) for another company to recreate this.

If you can't create a real economic moat, then you need to be able to lock people into your business, and make switching costs prohibitive that so competitors can't easily be stood up.

Both Uber's ride-hailing business and Grubhub's food-delivery service don't fit either of those criteria.

As we've seen with all the startups that have popped up across the globe that offer both services, creating a logistics engine to match restaurants, delivery people, and customers for Grubhub isn't hard. And matching drivers and customers to go from location to location is the exact same. There's no proprietary technology here.

And as drivers, restaurants, and customers show, these marketplaces have no ability to lock their suppliers or customers in. Almost every restaurant, driver, and customer is on multiple platforms, and has little loyalty to one versus another.

As such, as much as people may be excited about Uber consolidating the food-delivery space, it's unlikely to change the economics of the business.

The merger talks stalled over the weekend, and we can't be sure if the two companies will be able to reach an agreement on price.

And as if to further highlight the issues, in the midst of the initial announcement last week, reports emerged that another food-delivery startup in Chicago just got funded. Tock is a delivery service targeted at high-end restaurants, much like Caviar.

Even with Uber's move, new startups will continue to pop up in this space... And that means it's unlikely Uber will be able to generate the returns investors expect.

We're still students of tycoon John D. Rockefeller...

We're still students of tycoon John D. Rockefeller...

In the late 19th century, his work in turning a small drilling operation into the juggernaut that was Standard Oil was no small feat, and it would certainly attract the public eye today.

We've written about Rockefeller's strategy in the past, including in the April 3 Daily Authority. That said, it bears repeating just what made Standard Oil the cash cow it was...

While the business started out as a small drilling location in Cleveland, Rockefeller quickly realized where the real money was in the oil industry – refiners.

To get from the drilling business to the refining business, Rockefeller and his company bought anything in their path – competition, suppliers, and customers alike. He quietly positioned the business along the entire oil supply chain, which allowed him to undercut his competitors before buying them out at a reasonable price.

While Rockefeller spent quite some time vertically integrating Standard Oil, his sights remained on the refiners.

Once he had the means to do so, Rockefeller focused his company's efforts on buying every refiner it could find. After the campaign, Standard Oil owned more than 90% of U.S. oil refining volume in the late 1800s.

It's important to understand why Rockefeller was so focused on the refining step. You see, refining is the critical stage where oil transforms from a commodity into value-added products like gasoline, diesel, and other usable products.

By owning and controlling this stage in the process, Rockefeller and Standard Oil had the ability to define the oil market and the distribution, whereas those "upstream" from his refiners only owned commodity oil.

Ever since Rockefeller took this stance about the upstream components of the oil supply chain, it has gained a reputation for being highly speculative.

Oil exploration and production (E&P) is often viewed as the land of "wildcatters," like in the movie There Will Be Blood.

The film depicts the life of a wildcatter as a somewhat freewheeling, high-risk/high-reward business. You punch big holes in the ground, hope for the best, and move on.

Meanwhile, the Rockefeller-type folks continue to own the midstream and downstream businesses like refining and distribution. These were, and still are, firms with recognizable brands and some level of tangible sustainable cash flows.

For all of these reasons, it appeared to be the peak of management hubris going against Rockefeller's advice in 2013 when Hess (HES) management decided to sell off the majority of its storage assets and close its refinery in New Jersey in favor of its wildcatting E&P business.

Almost immediately, this proved to be a damaging decision when oil prices cratered in 2014 and beyond.

That said, the point of entering the wildcat segment of the industry is the high-risk/high-reward potential.

By focusing its efforts on the strongest oil basins in the country, Hess had the opportunity to mobilize its assets and reap massive rewards if it was successful.

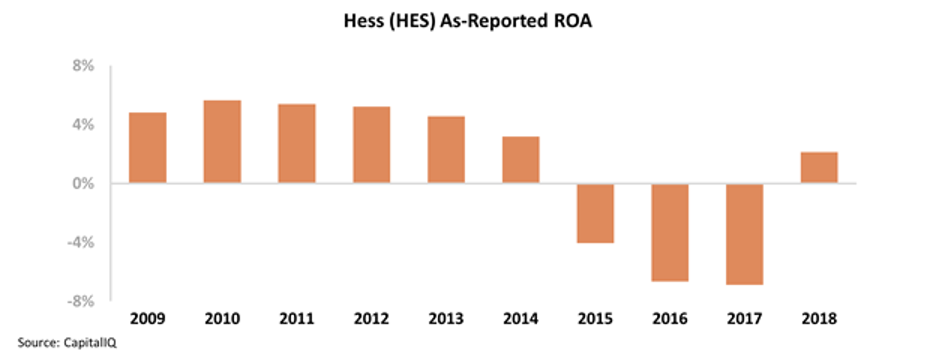

Following several weak years, it looks like the company was finally capitalizing on its strategy in its most recent fiscal year. After three consecutive years of a negative and declining return on assets ("ROA"), Hess finally turned a small profit in 2018 with its new strategy... yielding a 2% ROA.

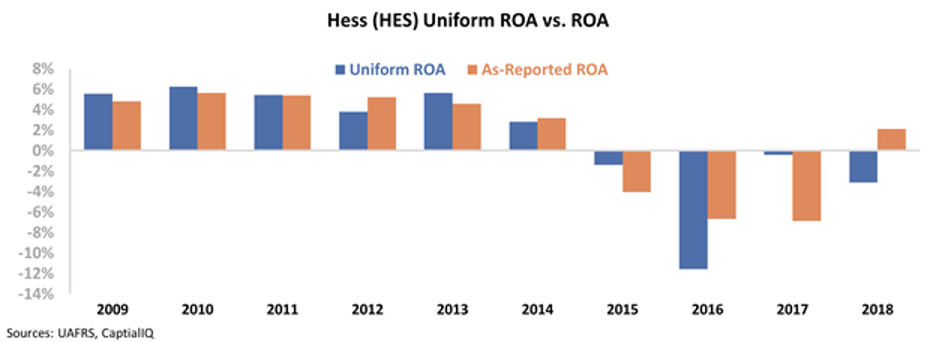

That said, the reality of the situation seems a bit less promising once you look at the right numbers.

After applying our Uniform Accounting metrics, we can see that Hess is still just a wildcatter chasing a profit.

As-reported metrics fail to account for misleading accounting practices like the impact of maintenance capital expenditures ("capex") on the company's property, plants, and equipment (PP&E) and goodwill. Once we make these adjustments, we can see that Hess still had a negative Uniform ROA last year, and this is likely to continue considering the recent oil price collapse.

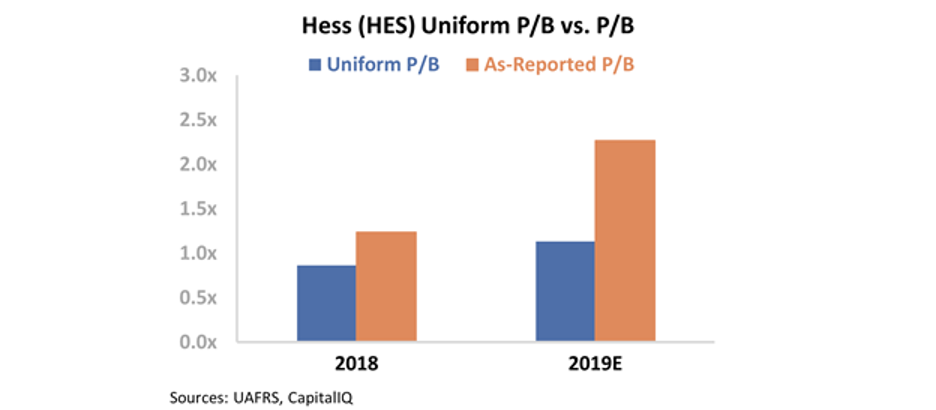

Furthermore, investors appear to be pricing in limited risk for Hess. Even after the last few months, the company still trades around a price-to-book (P/B) ratio of 1 – implying investors aren't worried about continued poor performance.

Once you look at the Uniform metrics, these valuations appear to be following the as-reported data suggesting that Hess is trending positively. When the company continues to struggle with its risky strategy, valuations may fall further to match the company's real performance.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

May 20, 2020

We let out a collective groan last week when the news broke about ride-sharing company Uber (UBER)...

We let out a collective groan last week when the news broke about ride-sharing company Uber (UBER)...