Bloomberg appears to have missed the forest focusing on the trees when talking about the pandemic debt risks...

Bloomberg appears to have missed the forest focusing on the trees when talking about the pandemic debt risks...

Last week, a Bloomberg editorial examined whether the pandemic could also lead to a financial crisis.

Regular Altimetry Daily Authority readers know that we've explained multiple reasons why the risks of the pandemic turning into a debt crisis are low, thanks to many aggressive actions taken to control liquidity and borrowing costs.

The Bloomberg piece highlights two key risks: how U.S. corporate indebtedness is at all-time highs... and the fact that if defaults increase, this could affect bank balance sheets.

The issue with the first statistic – which is based on non-financial corporate debt as a percentage of GDP – is that it doesn't look at the cost to service that debt. Since interest rates are at historically low levels – and likely to remain at those levels for the foreseeable future – companies can handle more debt.

In 1981, corporate debt was roughly 30% of U.S. GDP. Today, it's nearly 50%... But the cost to borrow for U.S. corporations has fallen from 20%-plus interest rates in the early 1980s to current rates less than 5% for many high-yield companies, and less than 1% for many investment-grade companies.

If we assume that businesses aren't ever going to pay down all their debts, of course they'd have more leverage in a low-interest-rate environment.

Additionally, for the concerns about bank balance sheets and if they can bear potential defaults... it's worth noting how healthy bank balance sheets were heading into this crisis – as we highlighted in the first Daily Authority link above.

This is yet another reminder to watch out for those in the financial media that may not be telling the complete story when quoting risks about an impending credit disaster. Keep following the Daily Authority and we'll report back if any of the real data about credit risk change... that's when we'd have cause for concern.

It's tough to make a good return by leasing assets...

It's tough to make a good return by leasing assets...

Inherently, all you're doing is spending on capital expenditures so other companies don't have to.

Many businesses would rather spread their payments over many months and years rather than buy all of their assets up front, hence the desire for other payment methods like leases and debt.

Due to the various alternatives to leasing an asset – including buying outright, or by borrowing debt and buying – the premium that a lessee is willing to pay for a lease tends to be low.

Because of the low barriers to entry, competitors also often offer to lease similar assets. Once again, this caps the potential return lessors can generate.

Leasing quickly turns into a price competition, which drags profits down to what it cost the company to fund its assets in the first place.

This means most leasing businesses end up earning something equivalent to the cost of capital, since lessees could just finance purchasing the asset at their cost of capital.

On the upside, leasing businesses can offer more stability than other business models. They'll often lease assets for multiple years with guaranteed monthly payments.

That provides a longer-term business outlook... and therefore, better planning capabilities.

DaVita (DVA) has been a cost-of-capital business for most of the past decade following this model. It provides kidney dialysis services for patients with serious kidney conditions, and distributes those services by leasing equipment to hospitals, for home care, and through its network of branded clinics.

All of this has led DaVita to earn average returns.

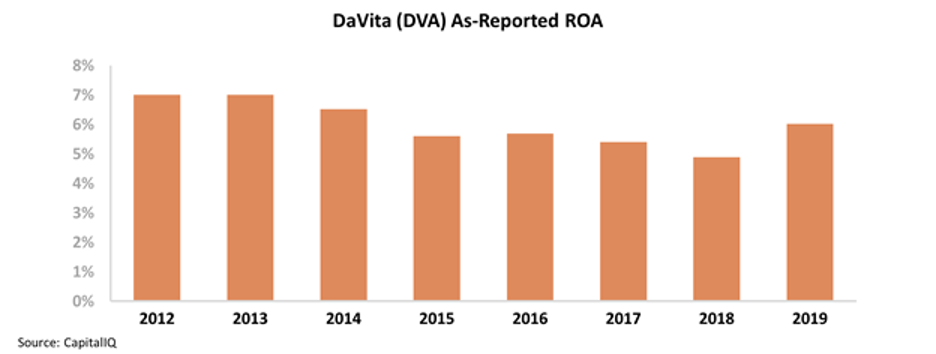

Since 2012, the company's return on assets ("ROA") has ranged between 5% and 7% – right around long-term average cost of capital levels of 6%. Take a look...

That said, the as-reported metrics for leasing companies like DaVita can be misleading.

In reality, DaVita has a lot more "value add" offerings than just leasing dialysis equipment. The company is a solution business and a partner with its clients on setting up and managing these assets, as well as helping patients with care.

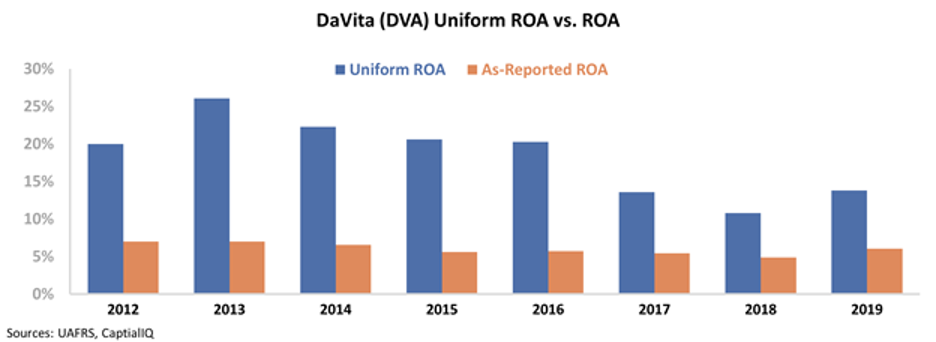

When we apply our Uniform Accounting metrics – which adjust for the effect of distortions like goodwill, operating leases, and interest expense – we can see that DaVita's returns have actually consistently been above the cost of capital since 2012.

In fact, the company's Uniform ROA hasn't fallen below 11% since 2012, and it peaked at 26% the next year – well above cost-of-capital levels.

You see, although DaVita's business relies on leasing, the company has found ways to add value on top of the standard leasing business.

As we said, DaVita leases its assets to hospitals and for in-home care, but it has also invested in ways to improve its treatment solutions to enhance patient outcomes.

With that component, DaVita isn't like a pure-play leasing business that can only charge its cost of capital. It has been able to differentiate itself rather than compete just on cost by improving patient outcomes – proving that it's able to both turn a profit and provide superior health care.

This all shows how as-reported metrics can actually lead to incorrect conclusions about a business. Investors looking at GAAP-based metrics would think DaVita was a commodity leasing business, not realizing just how profitable its value-add services are... But through Uniform Accounting, we can see the real story of higher returns.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

July 8, 2020

Bloomberg appears to have missed the forest focusing on the trees when talking about the pandemic debt risks...

Bloomberg appears to have missed the forest focusing on the trees when talking about the pandemic debt risks...