Silicon Valley is drying up...

Silicon Valley is drying up...

It's no secret that tech funding has cratered this year. Inflation and rising interest rates have created the perfect environment to stunt Silicon Valley's growth.

Tech investment dropped 23% from April to June, according to market-research database PitchBook. There were just 92 initial public offerings ("IPOs") in the first half of 2022. That's down 88% from last year. Investors are moving out of tech stocks in droves.

These declines are a mirror image of the 2010s tech boom. Back then, investors dumped money into companies like Airbnb (ABNB) and Uber Technologies (UBER) to create the household names we know today.

But today, the pendulum is swinging the other way.

People are realizing that betting exclusively on asset-light businesses isn't sustainable. Now, folks are starting to invest elsewhere... in industries like manufacturing.

Big venture-capital shops like Sequoia Capital and Lightspeed Venture Partners are cautioning startups to prepare for a tough winter. They think their books could shrink from this downward trend.

And it's not just startups and venture-capital investors that could feel the pain. The decline could also hit the banks that back tech companies... like SVB Financial (SIVB).

SVB Financial owns Silicon Valley Bank – the premier bank serving the land of innovation, as its name implies. As one of the original investors of this tech boom, it has a front-row seat to the tech-stock show.

That means SVB's performance is a useful gauge of the tech sector's health...

That means SVB's performance is a useful gauge of the tech sector's health...

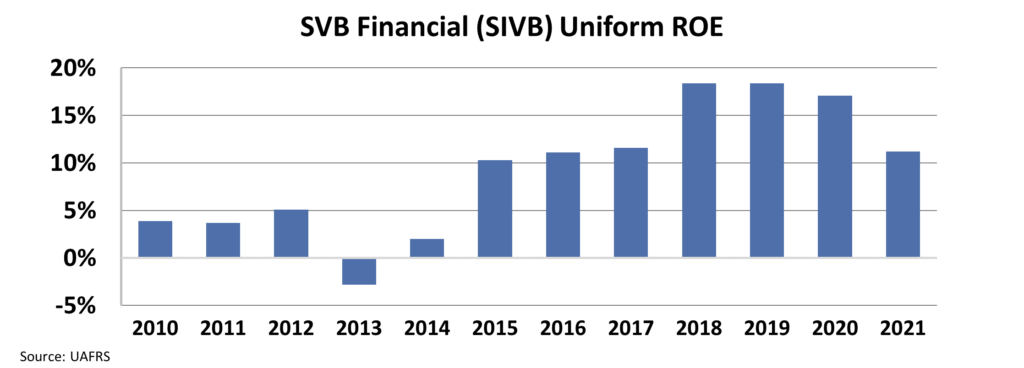

SVB is a financial-services company, so we look at return on equity ("ROE") to gauge its performance. That's because its "assets" are investor deposits... not physical things like machinery or inventory. The bank lends out these deposits, or its equity.

When looking at SVB's Uniform ROE, it's clear that the company has been improving over the past decade.

From 2010 to 2014, this was a low-return business. Its ROE hovered below 5%.

However, Uniform ROE climbed above 10% in 2015 and kept improving... reaching just below 20% from 2018 to 2020.

This trend shows how SVB was able to ride the tech-investment boom. But its 2021 returns also indicate a potential warning sign. Uniform ROE fell from 17% to just 11% in a year.

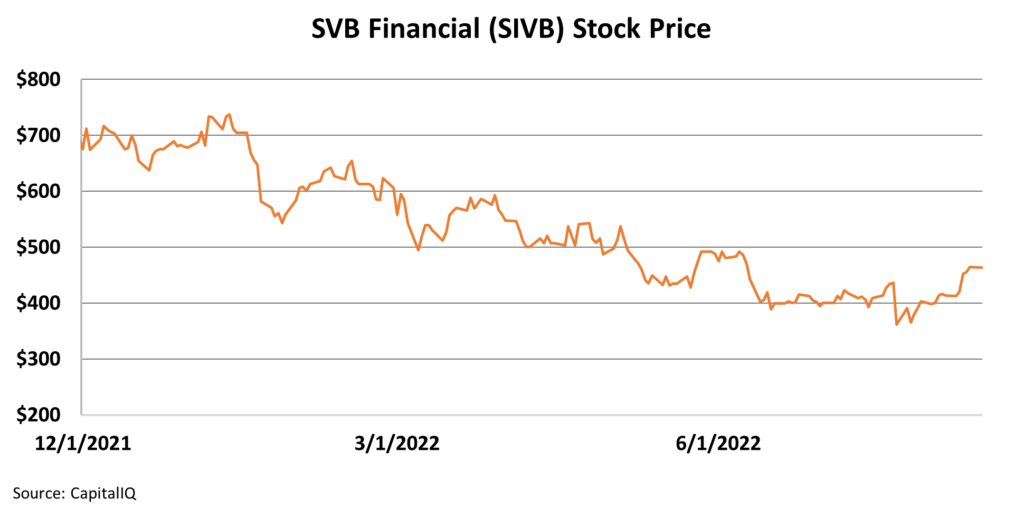

Right as we entered 2022, the market started catching on. SVB's stock is down 32% this year.

Such a large drop is a lot for investors to process. Some folks may think the stock is still in a tailspin. Others might wonder if it's a good buy now.

To figure out if investors were right to sell, we need to understand valuations.

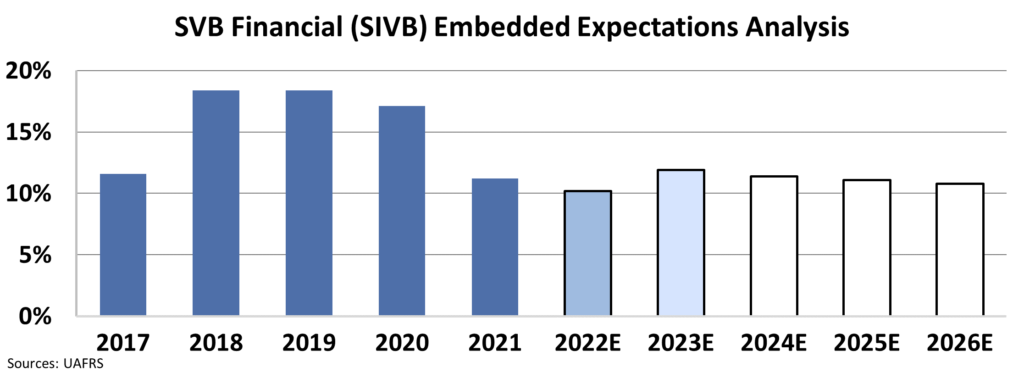

By using our Embedded Expectations Analysis ("EEA") framework, we can see what investors expect this company to do at its current stock price...

Stock valuations are typically determined using a discounted cash flow ("DCF") model. The DCF model makes assumptions about a company's future and produces the "intrinsic value" of a stock.

But here at Altimetry, we know models with assumptions based on distorted metrics from generally accepted accounting principles ("GAAP") only come out as garbage. Instead of relying on GAAP, we use the current stock price with our EEA to determine what the market expects.

Take a look...

The market expects returns to plateau at just above 10% going forward.

Frankly, 2018 through 2020 were historically good years for the bank. And 2021 seemed like a correction back toward normal operating levels. The market seems to get that. Investors are pricing Uniform ROE to stay around long-term averages for a good bank.

SVB has the potential to surprise investors with another historic cycle... But right now, you should watch out. Silicon Valley is contracting, not growing. Valuations will likely continue to reflect that.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

August 16, 2022

P.S. We received a great question from one of our readers, Bruce. He wasn't sure about our comparison between 2022 and 1945 to 1950...

I am not certain the comparison to the late 40s is valid for the following reasons:

- The U.S. was the only industrial nation left standing with essentially no competition.

- The U.S. had an abundance of very cheap oil, gas, and electrical energy.

- The consumer had no debt and large savings accumulated during the war.

- The labor force was young.

- The labor participation rate was high.

All of these factors supported a rapid growing economy. I don't believe any of these factors apply today.

Thank you for your thoughts on protecting our nest egg in today's economy.

We thought this was a great question and we appreciate all the feedback we've received from readers in the past month and a half. So we wanted to take a moment to address Bruce's comments point by point...

- Due to China's and Russia's recent actions, the U.S. looks more and more like the only investment and economic partner much of the world can trust. Its position in the center of the global economy is getting stronger, not weaker.

- The U.S. has an abundance of very cheap oil and gas... with massive production, favorable prices, and impressive reserves thanks to the shale renaissance.

- As we've mentioned recently, consumers currently have very healthy balance sheets and income statements. Absolute levels of savings reached staggering heights in the midst of the pandemic. Consumer credit metrics remain healthy, with limited defaults and low debt burdens across the U.S. economy.

- The labor force in the U.S. is still growing and young. Among developed economies, the U.S. has one of the youngest labor forces. It has one of the highest percentages of people under age 20.

- The level of labor participation isn't actually the most important driver of economic growth. Rate of change in labor participation can, however, impact how much demographic changes benefit or hurt an economy.

Right now, the participation rate sits closer to historic lows, at least relative to the era since women fully entered the workforce. As much of the Baby Boomer impact washes out, the balance of workforce participation will shift higher in the coming years. That's great news for the U.S. economy.

All of Bruce's points actually make us even more confident that we have the right analogy here. Now, based on the key issues we've examined in recent weeks, we'll be waiting for the economy to really take off... like it did from 1950 to 1970.

Silicon Valley is drying up...

Silicon Valley is drying up...